|

We hope you enjoy this series where we meet and get to know employees from across campus. Would you like to be featured? Contact us at campusnews@csufresno.edu.

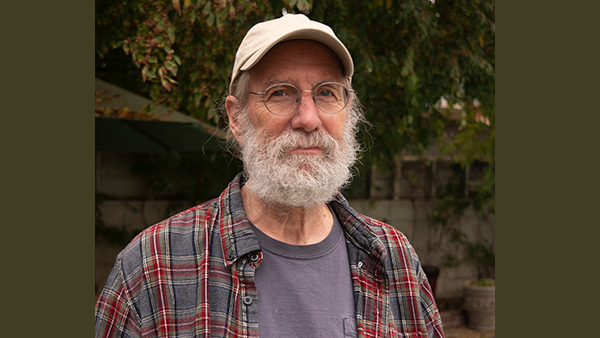

Name: John R. Hales

Title: Professor

Department: English

Academic Degrees: Ph.D. in American Literature and Culture from SUNY Binghamton

How long have you worked at Fresno State? I began teaching at Fresno State in 1985, the year I finished my Ph.D. at SUNY-Binghamton (and a year of teaching at Vassar College). So, it’s been 37 years.

What courses do you teach? My first courses were a mix of American literature, lower- and upper-division writing courses and English teacher preparation courses. I taught a number of topics courses as senior seminars, and those included American wilderness literature, American utopian literature, literature of the American farm, and nature and wilderness literature. I began coordinating the single-subject English teaching credential program in my second year, and in addition to teaching the department’s English methods and materials course, I supervised student teachers. Teaching students heading for a secondary teaching credential — along with working with some amazing teachers as campus coordinator of the California Literature Project — taught me so much about my own teaching I might not have learned otherwise.

Then, I began publishing essays in literary journals, and started teaching creative nonfiction writing workshops in the English department’s Master of Fine Arts Program in creative writing. I’ve been teaching undergraduate and graduate creative writing classes ever since. I’ve continued to teach American literature courses, and every once in a while, a graduate seminar in American nature writing, which connects my writing and teaching in ways I continue to be grateful for.

In addition to your nonfiction book, “Shooting Polaris: A Personal Survey in the American West,” what are your most notable publications and accomplishments? Much of my earliest published work explored my experiences working in the wilds of southern Utah as a land surveyor with the Bureau of Land Management through the 1970s, and these essays evolved into chapters in “Shooting Polaris.” My writing since then has focused on other subjects and experiences — for example, growing up in a Mormon, hunting-and-fishing foothill neighborhood in northern Utah; volunteer work with a telephone helpline in college; experiences raising a family with my wife, Connie Hales, through graduate school on teaching assistantships and student loans. Some of these publications were recognized with a Pushcart Prize, the Missouri Review Editors Prize, and a number have been listed as Notable Essays in the annual Best American Essays anthology.

I have plenty of drafts in various stages of completion I’m planning to return to when I become fully retired in January. I’m working on essays about my early teaching experiences in the heady days of post-1960s innovations, and I’m excited about a project that explores the way American attitudes concerning the use of military weaponry for sporting purposes have changed over the years (culminating in the current popularity of the AR-15), reconciling my own teenage hunting experiences with the very different gun culture of today.

What are you most passionate about, as an educator and as a writer, and why? The crucial importance of literature — what the best writing offers its readers, and the high bar it sets for writers. I’ve been teaching long enough to have seen, and been gratefully educated by, evolving attitudes toward the canon, the “great books” idea that narrowed not only the authors and books on the list, but tended to also narrow the relevance of literature to a wide range of human experience. I’m grateful to have had my own reading and teaching expanded by opening the doors wider, and the bookshelf longer, and more inclusive. My career as a teacher has also benefitted from opening the classroom doors of colleges and universities to students from increasingly diverse backgrounds, which has made the university classroom a much more profound and exciting place for teachers and students alike — nowhere as dramatically as here at Fresno State.

The constant, of course, has been reading, and it feels like I’m finally getting close to understanding what literature is, and what the best, most ambitious writing contributes to the world. In my graduate literature class this semester, a form and theory course for MFA students, we’re reading literature written from a wide range of experiences and perspectives, from Frederick Douglass to Gloria Anzaldúa, including a book by my former student here, Ashley Wells, who recently published her debut book. Students in my graduate writing workshop are writing literature of their own, powerful and publishable explorations of their experiences involving immigration, gender and sexuality, economic inequality, and other subjects representing the intersection of the personal and the political. My undergraduate students in a senior seminar are reading a work straight from the canon — Herman Melville’s “Moby-Dick” — and finding significance in a time and place distant from their own experiences, and also finding much to contest and question.

All this reminds me of what literature can accomplish, whether reading what’s included in the canon, or more recent, or previously overlooked, works of beauty and ambition. Or as students of writing, taking on the same awesome task of exploring their experiences for meaning, grappling with the biggest questions we’ll ever face, and what we’ve always found at the core of any great written work, from Gilgamesh to the powerful essays my students are bringing to workshops and publishing now in magazines: writing that helps us understand more clearly what it means to be human.

What is a memorable moment you had in class, and what do you think that reveals about your teaching style? I can’t tell you how grateful I am that one of those memorable moments unfolded just a few weeks ago. My students had been making their way through Melville’s lengthy book steadily, sometimes grudgingly, and always faithfully, with a variety of discussions, back and forth with me in their reading journals on Canvas, and small-group discussions during which they brought their personal questions and insights to each other, and then to the whole class for further discussion.

We’re all masked, of course — a simple gesture that has allowed us a level of classroom collaboration and engagement we can only approximate via Zoom, or other online platforms — so when my students break into small groups, the noise level rises substantially so as to be heard through their masks, and then above the din raised by other groups raising their own voices. On this day, I’d been wandering from group to group, loitering and eavesdropping, and trying not to add my own too-professorial voice (sometimes the best teaching involves just getting out of your students’ way!), and I stopped to just listen to the general roar, and contemplated for a moment this wonderful fact: my well-prepared and opinionated students were engaged in a variety of intense discussions about what was actually going on in a particular chapter (not always clear, in “Moby-Dick”), asking and answering each other’s questions about what a specific passage meant in terms of the book so far, making comparisons and connections with other works we’d read before beginning this one, and then comparing Melville’s characters’ motivations and admittedly bad choices in terms of their own lives and choices.

This class, to me, was wonderfully representative of Fresno State students, which meant the widest possible variety in terms of backgrounds and life experiences — 21-year-old English education majors just a year away from running their own classrooms, single parents weighing child-care complications and long commutes, an Iraq war veteran also aiming for a career in teaching, first-generation students majoring in the literature and language they were the first in their family to speak; a classroom full of students representing a rich diversity of cultures and ethnicities that contribute what seems like every possible perspective to considering a work of literature, all this reflected in their writing, and in the kind of discussion I was pausing that day to marvel at, and to be profoundly grateful for.

These moments are not necessarily routine — my students sometimes tend to find other things to talk about when grouped with each other, and some days even the hardest-working students won’t be able to find something to really engage with in the text we’re reading, or their writing might not rise to the standard they’d set in other written work. Still, my experiences teaching elsewhere has shown me that this kind and degree of engagement wouldn’t happen anywhere else, in classrooms not favored with this layered mixture of cultural richness and complexity, and individual experience and insight. I’ve been reading and re-reading Melville’s book for years, and still, literally every day in this semester’s class, my students show me something I hadn’t noticed before, or respond to their reading in a way that gives me an entirely new perspective on the work.

|

|

|

In your spare time, you enjoy repairing bicycles in your garage at home. How did you discover this hobby, and why do you think it has become such a habit? I grew up with bicycles, and could do minimal repairs and fixes — flat tires, bent fenders. But my reacquaintance with bikes that has become a kind of obsession began with my first full-time teaching experience at a Salt Lake City high school when I became one of the faculty sponsors of the school’s bike club. The main sponsor was a guy who really did know everything about riding and repair, and I learned along with our students how to rebuild derailleurs and pack wheel bearings. This culminated in taking 15 students on a 150-mile spring break bike tour through southern Utah, certainly memorable, and a little terrifying when I think about it, a string of unevenly skilled high school students spread out along a half mile of backcountry roadways.

When my wife Connie and I moved to upstate New York and were trying to raise a family on meager TA wages, I appreciated having one thing in our lives that we didn’t have to pay somebody to fix. In the same way Henry David Thoreau explains his efforts at self-sufficiency by telling us in “Walden,” “I was determined to know beans,” I was determined to know bicycles, and by the time I finally built my first bike wheel from the ground up — the second, actually; I overtightened the first wheel I’d built, and it exploded into a mess of bent aluminum and twisted spokes — I felt like I’d accomplished something.

After we moved to Fresno and began teaching at Fresno State, I continued to depend on a bike for commuting, but didn’t really return to building bicycles until some years later, when our kids began having their own kids, and I began building bikes for our grandkids, as well as way too many bikes for myself. I found projects at garage sales, thrift stores, and an amazing junkyard just off west Belmont that sadly has given way to a housing development, and in particular by bidding on bikes in various stages of disrepair at Fresno State’s Warehouse and Property Services auctions, along with other university surplus. As a result of my winning bid a few days ago, I now have a rusty Schwinn clamped on my bike stand, awaiting some serious dismantling and rebuilding.

In what ways is repairing a bike similar to, or different from, teaching and writing? It’s good for teachers to become students from time to time, particularly in areas that stretch our boundaries of confidence and competence. Like many of my colleagues in the English department, I grew up a voracious reader, and writing came relatively easy to me — at least until I began writing for publication. But I’m not a natural mechanic, and having to start from scratch on repairing or rebuilding a bicycle, reminds me routinely of how often learning is accompanied by frustration, failure, and self-doubt.

Working on bicycles reminds me that coaching is perhaps the most useful model for teaching language arts on any level. A lecture, for example, approaches literature and writing in exactly the wrong way — we’re not delivering information, or offering a product; we’re teaching a process, and students need to write and to read, to encounter their own specific challenges in drafting, and interpretation, to arrive at the specific problems or quandaries that a teacher might be able to address, helping the student take on the next challenge with a better sense of what might lead to a more successful piece of writing, or response to literature that might lead to deeper levels of engagement and insight.

Each beat-up bike I set out to rebuild presents a new set of challenges, and each time, I experience what it feels like to be a little in over my head, and searching for ways to solve a problem that isn’t responding to my still-amateur efforts. And when I really need to empathize with my students’ challenges, I turn my attention the old Fiat I’m attempting to rebuild, climbing an even steeper learning curve.

Working on bikes also taught me just how crucial good writing is, and how rare, when it comes to writing that isn’t necessarily literature, but at times perhaps even more essential. For example, building a bike wheel from a hub, a rim, and a pile of spokes is, for me at least, daunting. And I took on this task without a mentor standing helpfully alongside, and offering sympathy and suggestions, and I must have read a dozen how-to guides that really didn’t help. I know we’ve all had this experience, whether it’s with a casserole recipe or online directions for unfreezing a laptop screen: written directions that are either too general and obvious, or only decipherable by a specialist. I finally found a pamphlet-sized guide that somehow anticipated my confusion and frustration, gave me clear instructions on how to lace the spokes from hub to rim, and then somehow communicated something of the artistry involved in getting it balanced, round, and true, more a matter of feel, of sensation, than anything measurable or definite. Any written work demands knowledge and confidence on the part of the writer, but also a real concern for the reader, a sense not just of what needs to be clear, but consideration of what your writing is setting out to do—and how the reader will be affected by the specific choices the writer makes in drafting, revision, and polishing for publication.

One big difference between teaching and writing, and working on bikes: a bike is a project that can be completed, one way or another. It’s a matter of turning a wrench, or patching an inner tube, and you can tell pretty soon whether the brakes work, or the tire holds air. Teaching lacks this kind of milestone, a place where you can say it’s finished. Any English teacher knows that there’s always a pile of unread and ungraded papers covering the desk, and no two classes are anywhere near alike. Every class session requires its own planning and review, and I’m still trying to figure out why yesterday’s class tanked, when the Monday class went pretty well.

I’ve learned that I sometimes need challenges that require a wrench, a specific part to fit an axle or derailleur, and a dependable way of finding out whether I turned the wrench too tight, or just right. Even so, I delight in the unending process of teaching and learning, the way a work of literature will never give you a specific answer, and writing can always be revised just so, tweaked until you finally have to send the damn thing out, knowing that for you and your students, engagement with the written word is a process of continual exploration and revision, rethinking assumptions and trying new ones on for size.

~ Compiled by Jefferson Beavers, communication specialist, Department of English

|